In 1800 the global population was about 1 billion people and by 1900 it had grown to 1.6 billion. In North America the largest city throughout that time, New York City, rose from 60,000 inhabitants to about 4 million. Over the same time London, England, the largest city in the world throughout the 19th century, grew from 1 million to over 6.5 million. Such rapid growth over such a long period brought huge problems to all cities, not least how to keep the population well fed, healthy and cool.

Although mechanical refrigeration was first demonstrated in 1834 (in London), it took almost 50 years for it to become a recognized industry. The earliest rudimentary mechanical ice-making plants were being installed commercially by the 1870s, and it was in the 1880s that the refrigeration industry started to blossom. For most of the 19th century when cooling was necessary to preserve food or provide comfort it came from ice that had been cut from frozen lakes and rivers during northern winters and had then been shipped to the cities, sometimes thousands of miles away, and carefully stored for months to preserve it until it was needed.

The earliest known long-distance ice shipping venture was from Boston to Martinique in 1806, but it took the entrepreneur Frederic Tudor

over 20 years for his venture to gain financial success. By then ice was being shipped from North America to Great Britain in huge quantities and the rest of the developed world was wakening up to the possibilities of trading in frozen water. By 1900, 1 million tons of ice per year were being shipped from Norway to England, much of it to serve the fishing trade along the east coast ports. A combination of rising prices, poor ice harvests during warm winters and improvements in mechanical technology caused a rapid decline in the trade at the start of the 20th century. In the port of Grimsby, on the east coast of England, the largest mechanical ice plant in the world was built in the period 1899 to 1900 and then further extended in 1907. At its peak in the 1950s the Great Grimsby Ice Factory produced about 1,200 tons of ice per day and served a huge fishing fleet with chunks of ice chewed from blocks in large crushers and fed by overhead conveyor to the trawlers at the dockside.

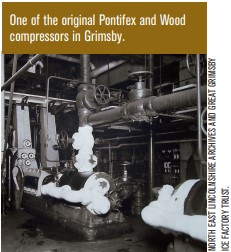

The original refrigeration system in the Grimsby factory comprised four ammonia machines manufactured by Pontifex and Wood of Farringdon, London, with boilers providing steam to power the compressors. This initial installation may have been completed by the English refrigeration firm Haslam, who had amalgamated with Pontifex and Wood in the 1890s but the 1907 extension was entrusted to the British Linde Refrigeration Company under the leadership of Thomas Lightfoot. The Linde compressors were reckoned to be the most efficient of their type and factory output increased from 300 tons per day to 500 tons per day. Factories like Grimsby were the death-knell for the natural ice transportation business. Even efficient operators reckoned they could lose up to 50% of the ice that they harvested from the frozen rivers during storage and transport and it became too difficult to compete with the reliable low cost supplies that were manufactured on the spot.