Last month’s column considered how the rapid growth of urban populations in the nineteenth century was the catalyst for the growth of the mechanical refrigeration industry. It is doubtful that those pioneers could have foreseen the diversity of applications for their new technology that is now used in everything from cryosurgery to high temperature heat pumps and is an essential utility in keeping society functioning.

Natural ice gave way to mechanically produced ice at the end of the nineteenth century, but the ice sellers were driven from the streets just a few decades later with the advent of the domestic refrigerator; initially with sulfur dioxide or methyl chloride and then with the new range of “safety refrigerants,” the freons. Although cooling was no longer delivered to the home in the form of a block of ice for the “ice box” our love affair with the simple ice cube continued. When I was growing up we had small plastic trays to fill with water and place in the freezer compartment to make ice cubes and a more recent innovation was a plastic bag divided into small pouches that could be filled with water and hung on the back of the freezer door. Each frozen pouch could then be ripped out of the bag when required. A novel use of this system was for freezing batches of concentrated sauce, where each pouch was one portion of sauce that could easily be added to a saucepan when cooking a casserole or soup. Now we have refrigerators with built-in ice dispensers to provide cubes on demand. These always make me wonder about the energy efficiency of the system. On paper these fridges are as good as the models on the market that don’t have automatic dispensers, but if the ease of delivery encourages an increase in use and the system is plumbed into the main water supply so there is no more fiddling about with trays of water then electricity use must surely go up steeply.

Another impressive but somewhat wasteful use of ice can be seen in the bars and restaurants of Tokyo. When a customer orders whisky on the rocks the barman will take a chunk of ice from his cabinet and attack it with a small pick until he has chiselled it into a perfect sphere that sits snugly in the glass. Of course, this means a cubic block of volume (2r)3 has been manipulated into a ball with volume (4/3)πr3. 8.0 has been reduced to 4.2; in other words, almost half of the block has been chipped away and runs down the drain as melt water. When a Japanese refrigeration equipment manufacturer needed a heat load to run their R&D test chamber they installed a small ice making plant

and ended up supplying half the bars in the neighborhood, making enough revenue along the way to make a healthy contribution to the research budget.

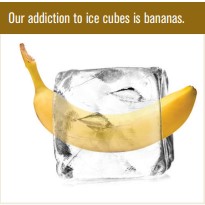

The value of cubed ice can be seen by the number of commercial facilities making it by the bagful. One high-end retailer told me that they reckoned to make more profit from ice cubes and bananas than any other product lines in their stores. When you consider the luxury items on offer, ranging from caviar and lobster through exotic fruits to expensive wines and chocolates this seems odd. The answer is that not everyone buys these other luxuries, which are expensive to make from expensive ingredients, expensive to ship and expensive to store, but everyone loves an ice cube which only takes tap water and a little bit of energy in a fairly simple automated process. Even at Christmastime the supermarkets will do a roaring trade in ice.